April 2013 I was allowed access to the National Museum of Scotland’s offsite storage facility to see a rather remarkable artefact in its collection. I was there to study a casing stone from the pyramids of Giza in Egypt. The casing stones have an angled front face that formed the outer surface of the pyramid. The front is triangular in form when viewed from the side, as opposed to the inner blocks which were left roughly hewn and were approximately cuboid. If we know the slope of one of the casing stones faces we know the side slope of all of the pyramid’s faces, and so they are of particular interest to archaeologists studying pyramid architecture. I intended to repeat some typical measurements of the stone in order to study it methodically, but what I found was quite unexpected, and constituted something of an archaeological breakthrough…

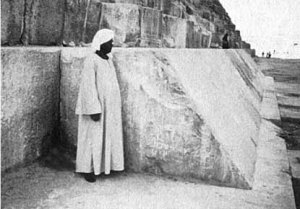

Giza casing stone catalogue number A.1955.176 at the NMS and Egyptian cubit rule

This stone was mined at the Tura quarries on the east side of the Nile 45 centuries ago, shipped across the river to Giza on the west bank, dragged to the pyramid construction site, carefully shaped with copper tools and lifted into place on the outside of one of the Old Kingdom pyramids. Its original architectural position on the pyramid remains a bit of a mystery as it was found in the mounds of debris on the north side Great Pyramid of Khufu by Waynman Dixon in 1872. Dixon was an English engineer who was carrying out investigative work at Giza for the Astronomer Royal for Scotland, Charles Piazzi Smyth [1]. These casing stones were stripped off the pyramid in the ancient past as they were very high quality stone and therefore useful for building in modern Cairo. Only a few fragments remain at the Giza site, and this example found by Waynman Dixon was unique in several respects.

Artefacts from Giza brought back by Waynman Dixon in 1872 including the Edinburgh casing stone

Smyth was interested in the dimensions of the Great Pyramid as he believed they may have had profound significance, and the stone was brought back to Edinburgh for him [2]. In fact the dimensions of the Great Pyramid do have significance, although Smyth was unable to understand the symbolism fully as he did not yet have an understanding of the technical systems used by the Ancient Egyptians such as the seked slope measuring system and the cubit length measuring system. 1 cubit was a standard measurement length used all over Ancient Egypt for measuring fields and constructing buildings. It was 52.35cm long during the Old Kingdom when these great pyramids were built, and this was broken down into 7 palms of 4 digits each [3][4].

cubit

In order to understand the pyramids and this casing stone in Edinburgh then, we needed to approach the study using these Ancient Egyptian systems. We can only understand the Egyptian achievements and the Egyptian artefacts by working from within their own systems of thought. Although I took along some modern tools, including a laser spirit level and a degree marked ‘gravity inclinometer’ (slope measurer), it was in fact the replica Egyptian cubits that revealed the most significant and interesting information regarding of this heavy lump of Tura limestone.

Once we managed to move it carefully out into the open from its storage position, I was able to see that it is substantially broken, probably due to having been pushed down the pyramid in the ancient past. Nevertheless, the three all-important worked faces are still partially intact and in good condition in places. These three surfaces are the flat base, the sloped front face and the flat top. I had hoped to measure the sloped face angle using the gravity inclinometer, which uses a weighted pendulum against which to measure the slope angle, but in fact the stone was on its side and so I could not use the inclinometer as had been intended. The stone was too heavy to turn onto its bottom face, on which it would have sat originally, but by using a variation of the technique shown on the diagram below (see photo), I was able to tell that the face was approximately at the correct angle known for the Great Pyramid, of 51.84 degrees. The limestone of the block was also surprisingly bright in color, almost silvery, especially the limestone dust on the surface. The Tura limestone from south of Cairo is thought to have been mined specifically for its light colored limestone, to be used for the outer faces of the monuments, so these two facts gave me confidence that we were indeed dealing with a genuine Giza casing stone.

Measuring the inclined face of the pyramid casing stone if it was sitting on its base

Below is a photo of the actual measurement taking place. Note that the accuracy of this technique is around 1 degree at best, and so it was carried out only to verify the known data rather than to establish new data. The top face is on the left of the stone in the photograph below, with the laser spirit level held flat against it. The inclinometer is being held against the front slope face. The red laser line shines a beam straight out parallel to the flat top side, and the blue lines show that a right angle was clearly formed at the intersection of this line and the pendulum line when it was held at the known pyramid angle. This means the stone’s face was sloped compared to the top surface by the expected pyramid angle which is known to be 51.84 degrees. The stone is broken in places, but these parts of the faces are intact, flat and smooth and so the measurement was legitimate, if of moderate accuracy.

Measuring the angle of the casing stone slope

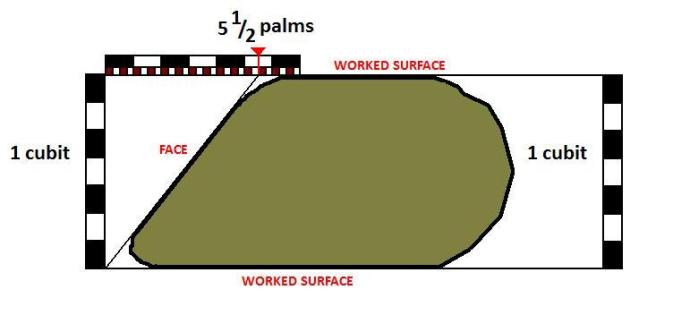

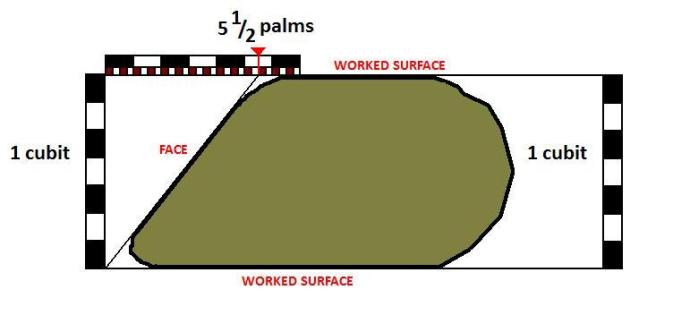

After this was done I brought the replica cubits into play, and this is when things began to get really interesting. On one of them I had already marked off 5 1/2 palms (you can see the small mark in the middle of one of the white palms on the cubit on the left below) as this is the known seked of the Great Pyramid . When used with another cubit the two formed a triangle with a seked slope face of 5 1/2. This known seked of the Great Pyramid corresponds to 51.84 degrees, the known ‘pyramid angle’. By placing the marked cubit (left) against the top surface I could use the second cubit as a vertical to check the size of the slope using the cubits. In this case the second cubit should touch the face surface at some point allowing a measurement. In fact, as it turned out, the second cubit was a little long and stretched right down to the lower edge of the block, almost meeting its lower corner. I wondered if the erosion of the lower corner of the block had rounded off that edge, so I placed a nearby flat unmarked plank against the bottom of the stone. I was surprised to see that the darker cubit (right) fit exactly between the upper white cubit and the plank, indicating that the casing stone was exactly 1 cubit thick. We checked the right angles with a square and they were all correct. To further check that this right angled triangle was the accurate design form, I extrapolated the front sloped face down to the plank by placing a cubit flat against the front slope face, and slid it down until it met the unmarked plank still held against the flat bottom. At the meeting point of these two, I marked off the plank with a pen, thus re-establishing where the lower corner edge of the original face had been before the corners had been broken off (NB: This was an extrapolation technique I have used before when measuring the base corner of a monument pyramidal foundation structure in Cyprus).

The seked triangle revealed when measuring the block faces with replica cubit rods

The diagram below shows more clearly what we are doing in the photograph above and what this seked triangle used by the Ancient Egyptians looks like. This task demonstrated that the block is in fact exactly one cubit in height and with the offset of 5 1/2 palms it corresponds pretty much exactly with what we know about the seked measurement system and the ‘pyramid angle’ of the Great Pyramid. The block is one cubit high and offsets 5 1/2 palms for each cubit rise – the very definition of a seked of 5 1/2.

Pyramid angle of casing stone block using cubit and seked system – Seked of 5 1/2

Knowledge of the seked system only came after Smyth’s time, thanks to another discovery made by a Scottish antiquarian, Alexander Henry Rhind. In 1864 Rhind was offered a remarkable papyrus recovered from the West Bank of Thebes that contained some of the oldest mathematical calculations known in human history. Rhind unfortunately died as he brought the papyrus back to Scotland, but the papyrus did complete the journey and it is now known as the Rhind mathematical papyrus [5]. It took several decades to translate and publish it and so Smyth was never familiar with its contents. It contained many examples of how to approach arithmetical and geometric problems, including, crucially, how to calculate the required and measured slope face of a pyramid. The Ancient Egyptian methodology for defining a slope face began with the architects choosing the desired base and height dimensions for the pyramid, measured in Egyptian standard cubits and then working out what the slope value was

Using straightforwards arithmetic, the Rhind papyrus shows us how the side slope of a pyramid’s faces can be defined numerically by working out its ‘seked’. This seked is the name the Egyptians used for their slope system. It is a little like modern day degrees and angles, or inclines quoted in percents like we see on road signs for steep hills. According to the Rhind papyrus, however, the seked slope consisted of the number of palms moved horizontally for each 1 cubit rise [6].

- Pyramid seked calculation – Problem 56 of the Rhind Papyrus

These experiments show how much information can be derived from ancient artefacts by using appropriate archaeological methods to study them and by understanding the cultural and technical systems of the people you are studying, This demonstrates the value of experimental archaeology as methodology. Basically, this is a large chunk of limestone, but when studied in the correct manner it can reveal substantial information about the cultural and technical systems of the Ancient Egyptians. But this particular angle or seked also has a more profound geometric significance, which is what makes this issue even more fascinating to study:

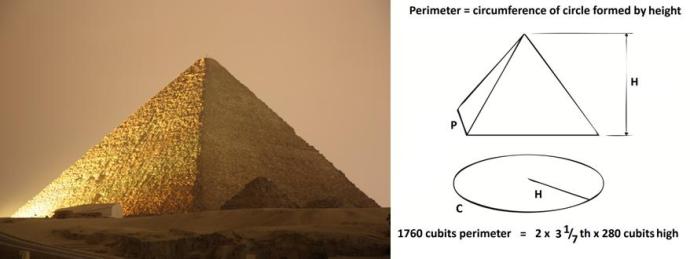

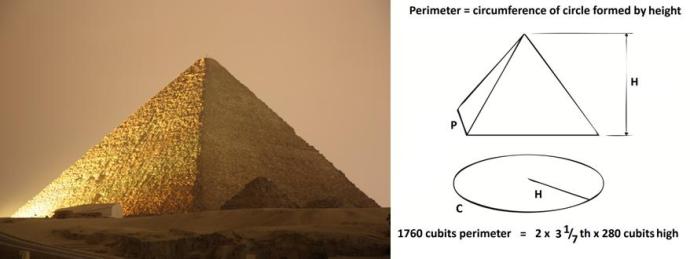

A pyramid having this face angle has a base perimeter equal to a circle formed by its vertical height

This relationship only holds for a pyramid of this precise angle. Smyth thought that this had been deliberate, but he then drew a whole series of unfounded conclusions about the significance of this geometric relationship. The great English Egyptologist Flinders Petrie followed Smyth’s work with a more scientific study and detailed triangulation survey of the whole Giza Plateau in 1882 [8]. He concluded that the circular relationship had indeed determined the choice of this particular slope with a seked of 5 1/2, but he also demonstrated that Smyth’s conclusions about what this meant were nonsense, and that the other geometric relationships Smyth had supposedly identified were unfounded or culturally and historically irrelevant.

Circular proportions of the Great Pyramid of Khufu at Giza

Petrie was certain that the circular symbolism had been intentional. In fact he wrote about in print this no less than five times through his long career, in 1883, 1885, 1890, 1925 and 1940. In Wisdom of the Egyptians [7], published in 1940, he wrote, correctly, that “…these relations of areas and of circular ratio are so systematic that we should grant that they were in the builder’s design”. He also found the same proportions and related numerical dimensions used in the construction of the pharaoh’s burial chamber in the Great Pyramid, again best understood when using the Ancient Egyptians’ own cubits. Other great pyramids such as the pyramid of Meidum and the Queens pyramids at Giza use the same proportions, and Egyptologists such as I.E.S. Edwards and Miroslav Verner agree with Petrie’s conclusion that these proportions had significance and were deliberately chosen because of their symbolic relationship with the circle [8][9]. My own contribution to this subject was to check all of the data again, and try and identify what this symbolic architectural choice meant to the Ancient Egyptians, within their own cultural systems of thought. In order to check Petrie’s data I studied amateur Egyptologist Jon Bodsworth’s analysis of the Great Pyramid’s dimensions, based on Petrie’s 1883 survey [10], as well as later surveys and surviving casing stones. He constructed a three dimensional model which included details of the heights of each core block layer and the slopes of the casing stones. His model is shown below with half the casing stones as they would originally have been placed.

Great Pyramid with half of the casing stones in place correctly proportioned

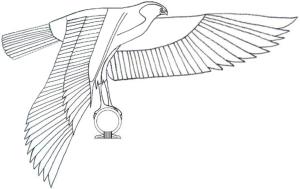

My own contribution to this subject matter then, has been to show what this architectural symbolism meant. The special proportions were a manifestation of a deep seated belief in the power of encircling protective symbolism, that was expressed in the architecture and the more portable material culture of the Ancient Egyptians of the Old Kingdom (on crowns, royal statues, fine furniture and precious vessels) [11][12]. Iconographically, this encircling royal protection was represented by a shen ring. The shen ring was often shown carried above the pharaoh by the royal patron god Horus, the falcon.

Typical arrangement of the royal god Horus with shen ring often seen flying above the pharaoh

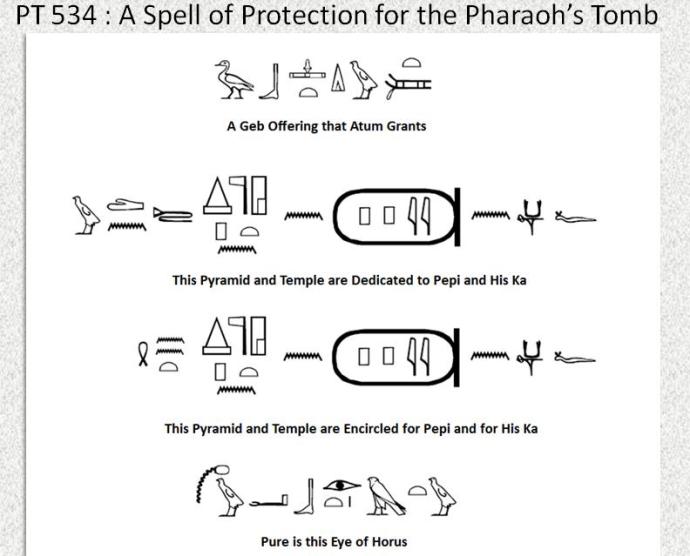

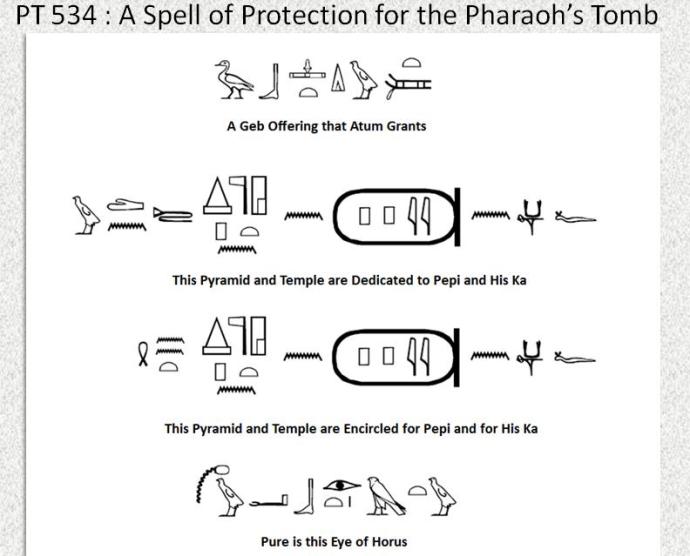

In this form the falcon was often shown flying above the pharaoh in reliefs, from as early as the Third Dynasty and many high status royal items from the Old Kingdom bore the shen ring symbol. This protective symbolism was manifested in the architecture, particularly within the all-important outer perimeters of the buildings that protected the pharaoh and protected the sacred space within from the dangers of the profane world outside. From the start of the 6th dynasty this symbolism was also expressed through texts on the walls of the funerary monuments. But the clearest textual manifestation of this symbolism with respect to the pyramids is undoubtedly Pyramid Text 534, a ‘spell of protection’ for the pyramid [13]:

This spell or prayer of protection is written on the walls of the entrance passage into the pyramid of Pepi I at south Saqqara and may describe the fundamental rituals involved with building this monument. The text starts with a ‘Geb offering’, which may allude to a foundation deposit made at the start of the construction as Geb is the god of the earth. This is followed by lines describing how the pyramid and temple are then ‘established’ and then ‘encircled’ to make them pure; an ‘eye of Horus’. The encircling here, using the word shen, implies that the pyramid is also protected by this action. It is difficult to tell if the casing slope angles of these later, smaller pyramids were the same as at Giza and therefore manifested the significant circular proportions, as they are much smaller and in ruins compared to the great pyramids of the 4th dynasty, but it is clear, through this text, that the protective symbolism endured and was expressed in new and innovative ways during the 6th dynasty. In fact, each pyramid of Egypt needs to be understood within the continuously changing historical and cultural contexts. They were, to some extents, designed and constructed using ‘ad hoc’ techniques [15]. Beliefs with respect to the death of pharaohs are inherently conservative, but the ways in which those beliefs were expressed changed with respect to the cultural context in which those expressions were made. These are the real secrets of the pyramids. The architecture embodied spells of encircling protection, in many different ways.

To understand the casing stone in Edinburgh then, we need to use the technical systems used by the 4th Dynasty Egyptians, we need to understand the architecture of the monuments in which they were used, and understand the beliefs held by those who commissioned, designed and built the monuments at the time. That includes understanding their measurement systems, their iconography and even their hieroglyphs, texts and ritual beliefs.

Hieroglyphs used for writing cubits, palms, digits and sekeds

Substantive arguments have been made, based on the evidence, that the Egyptians were not able to calculate the circumference of a circle to this degree of accuracy, however, the latest analyses show that the evidence has been misinterpreted or treated in isolation, and when it is revisited and properly examined, it shows that the textual evidence and the architectural evidence do indeed agree with each other and do support the above conclusions that the Old Kingdom Egyptians were well able to calculate circumferences and perimeters to this degree of accuracy [14].

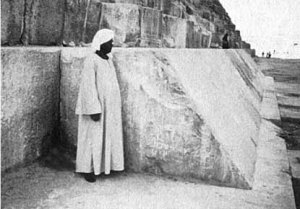

One final mystery remains, however. Heavy though this casing stone is, it is small compared to the giant sloped stones still in place along the northern side of the base of the Great Pyramid.

Base layer casing stone from Great Pyramid of Giza

Most of the fine casing stones were stripped off the Great Pyramid and recycled to build Cairo during the medieval period, but a few of the huge bottom row remained in place, protected under the mounds of fragmented stone that had gathered along the edges of the pyramid over the centuries. The question was then, was this Edinburgh stone actually from the Great Pyramid at all, or did it come from one of the similarly proportioned queens pyramids nearby, which were also built at the same time as the Great Pyramid, but which seem to have used smaller casing blocks of around this smaller size. This would not impact on the conclusions of our analysis regarding circular symbolism, as we know that both king and queens’ pyramids were similarly proportioned with a seked of 5 1/2, but it is interesting with respect to the architectural provenance of the Edinburgh casing stone.

In fact the answer to this question becomes clear if we refer to the surviving casing stones still in place on the upper levels of Khafre’s pyramid, near the peak. As Mark Lehner described with respect to the second Giza pyramid of Khafre, [15] ‘the casing stones at the top of the pyramid are much smaller – about 1 cubit thick (c. 50cm/20 in)’. Our example from Edinburgh then, from the north side of Khufu’s pyramid, is most likely to be a rare survival – an upper level casing stone from Khufu’s pyramid, perhaps dropped and lost or forgotten during removal in Antiquity or the medieval period. This stone, however, is not ‘approximately’ 1 cubit tall, it seems to be precisely 1 cubit tall. This level of precision would fit with what we know from the rest of the architectural and archaeological remains of the Great Pyramid. The standards of workmanship and consistency were greater here than for many, if not all, of the later pyramids. It is quite possible that all of the upper level casing stones of the Great Pyramid of Khufu were precisely 1 cubit tall, to make the finishing of the peak of the pyramid more manageable, and to ensure that high levels of precision and control could be maintained over the final form of the structure. Our Edinburgh casing stone, therefore, is probably not just a Great Pyramid casing stone, it is probably an upper level Great Pyramid casing stone, from up near the summit of this incredible monument, 146 meters high when completed.

All in all then, this unadorned block of broken stone has truly remarkable historical and scientific significance, both regarding the ancient world, the 19th century world, and now in the 21st.

Thanks to Margaret Maitland, Curator of the Ancient Mediterranean at National Museums Scotland, and Alan Jeffreys of Egyptology Scotland for help in this research project.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

Additional notes:

Here is a link to Smyth’s description of the casing stone from his long, rambling and largely erroneous book devoted to the Great Pyramid, first published in 1874 [16], two years after the casing stone was brought back to the UK. We can see from the measurements he records that Smyth had indeed measured the vertical height of the stone, and noted that height in inches. He was aware of the length of the real Egyptian cubit by that time (as opposed to his imagined ‘sacred’ cubit), and so it is surprising that he did not see the significance of this dimension, particularly as he was clearly obsessed with measurements and units. Why did he miss this? Perhaps it was because he was not using a cubit to actually do the measurement. It was only by physically having the cubit there in my hand that I noticed the correspondence. I am also aware of the Egyptians’ own seked system, and so when I noted the correspondence I was able to mentally refer to the Egyptian texts that confirmed the significance of this particular dimension to slope measuring. Smyth did not have this luxury, as the seked system examples from mathematical papyri had not yet been translated or understood in his time. The final, and perhaps most significant reason that he missed the presence of the real system in the block’s measurements is because he was clearly busy trying to confirm the presence of his own imagined system of ‘sacred cubits’ and ‘pyramid inches’ in the width of the block. He actually notes the width of the block as possibly related to his imaged system and flawed understanding of the pyramid’s architecture, while at the same time being completely oblivious to the fact that actual measurements utilized by the Old Kingdom builders were staring him in the face. Hindsight is 20-20 as they say!…

Here is a link to a recently published discussion regarding the practical challenges faced by the Ancient Egyptians when installing these casing stones, as opposed to the mathematical, metrological and symbolic issues that I have discussed above. Jean Pierre Houdin is a French architect turned Egyptologist (yes I think he deserves the designation) who probably knows almost as much as I do about pyramid building ;), and who has also dedicated his life to studying these amazing monuments. He is interviewed by Keith Payne, owner of Em Hotep BBS, a dynamic and positive discussion page devoted to disseminating archaeological and Egyptological information to the wider readership.

Note: Other than the black and white casing stone photograph and Jon Bodsworth’s 3D computer model image, the photographs and diagrams on this page remain the property of, and copyright © National Museums Scotland and/or David Lightbody.

————————————————

References:

[1] Brück, H.A. & Brück, M. (1988) The Peripatetic Astronomer: the Life of Charles Piazzi Smyth. Bristol: Hilger

[2] NATURE , Dec. 26, 1872, pp 146-9. THE GRAPHIC, Dec. 7, 1872, pp 530 & 545

[3] Arnold, D. (1991) Building in Egypt. Pharaonic Stone Masonry. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp 251

[4] Petrie, W.M.F. (1883) The Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh, London: Field and Tuer, pp 179

[5] Chace, A.B. (1926) The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus, Ohio: Oberlin

[6] Gillings, R. (1972) Mathematics in the Time of the Pharaohs, New York: Dover

[7] Petrie, W.M.F. (1940) Wisdom of the Egyptians, London: British School of Archaeology in Egypt and Egyptian Research Account ; [vol. LXIII], pp 30

[8] Verner, M. (2003). The Pyramids: Their Archaeology and History. Atlantic Books, pp 70

[9] Edwards, I.E.S. (1979). The Pyramids of Egypt. Penguin. pp 269

[10] Petrie, W.M.F. (1883) The Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh, London: Field and Tuer

[11] Lightbody, D.I. (2008) Egyptian Tomb Architecture: The Archaeological Facts of Pharaonic Circular Symbolism. British Archaeological Reports International Series. Oxford: Archaeopress

[12] Lightbody, D.I. (2012) The Encircling Protection of Horus in Proceedings of the Twelfth Annual Symposium Current Researches in Egyptology, 2011, University of Durham Oxford: Oxbow, pp 133-140

[13] Faulkner, R.O. (2007) The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts, Stilwell, Kansas pp 201, 202

[14] Cooper, L. (2011) Did Egyptian Scribes Have an Algorithmic Means for Determining the Circumference of a Circle? Historia Mathematics Vol 38, pp 455-484

[15] Lehner, M. (1997) The Complete Pyramids, Thames & Hudson pp 122, 123

[16] Smyth, C.P. (1874) Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramid Including the Most Important Discoveries up to the Present Time. London: Isbister. pp 489